Table of Contents

Dedication

To My wife of 68 years

Madeleine Huppert Kingsbury

Without whose unfaltering love, understanding and encouragement,

this book would never have been completed.

Inside Front Jacket

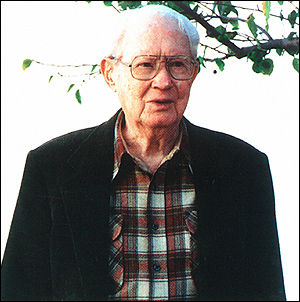

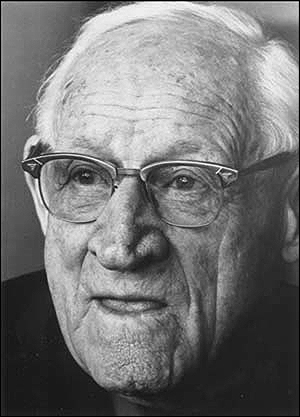

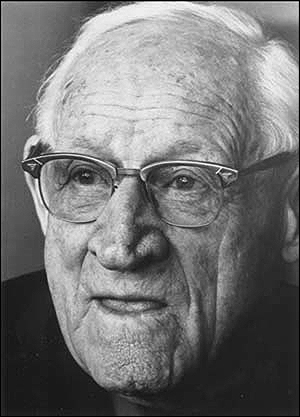

Lilburn Adkin Kingsbury

(October 14, 1884 - July 1, 1983)

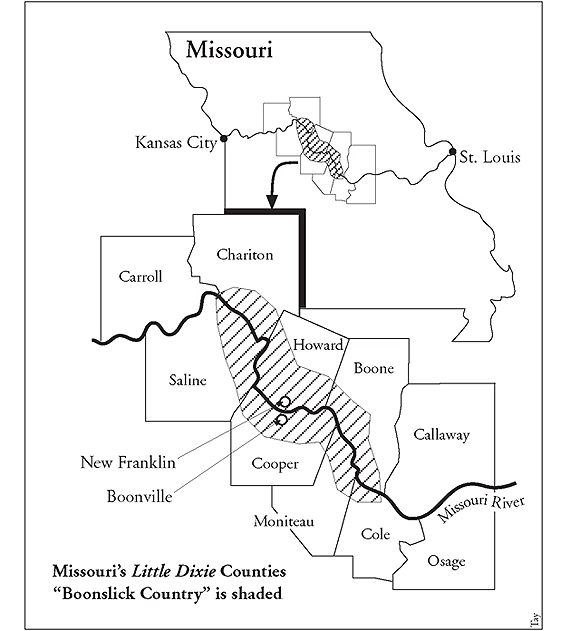

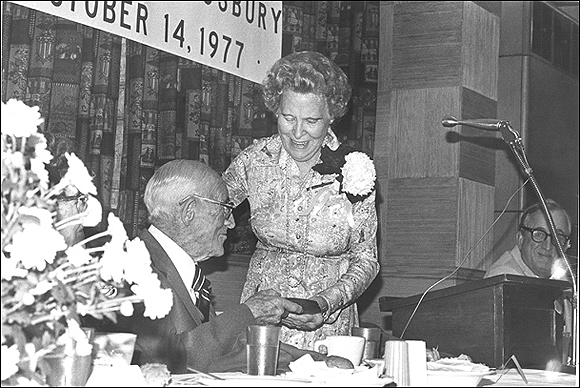

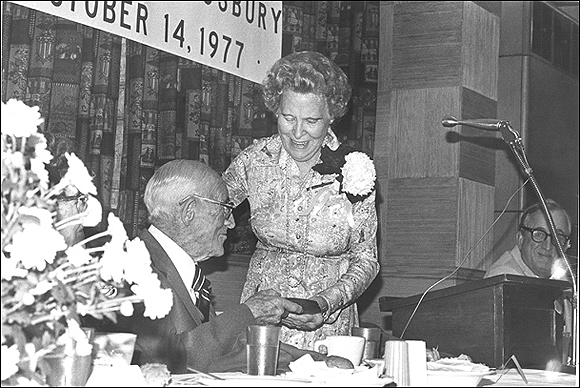

Alex Hailey, author of Roots wrote: “When an old person dies, it is like a small library burning.” This was not true of Lilburn Adkin Kingsbury. I found his writings to be a small but very precious library. These writings include much of his historical research covering 150 years of life in Missouri’s historic Boonslick country. They tell much of the mores and activities of its interesting people. I believe the nucleus of this material should be preserved as Lilburn’s legacy to those who shared his love for the historic area. From early childhood Lilburn always had one or more hobby horses to ride. These included collecting antique furniture, pressed glass, bottles, jugs, clocks and ultimately buttons. Other hobbies were genealogy, history, talking to groups, and writing articles and columns. All these are described voluminously in his principal hobby, letter writing. His history hobby led to his becoming the first president of the Boonslick Historical Society. In 1977 the Boonslick Historical Society, relatives, and friends gave Lilburn a surprise 93rd birthday party honoring him for his forty years of service to the society and his many contributions to the community.

–Warren Taylor Kingsbury

Inside Back Jacket

Excerpts from the Letters from Lilburn

“In anticipation of the hanging excitement, a group of men arranged for an excursion train to be run from Sedalia to Boonville to accommodate those who wished to witness the event....”

• • •

“The next day our minister felt impelled to tell Mrs. Flake that his wife cried all night after seeing her skating promiscuously with all those men....”

• • •

“The sale was halted while someone whispered in the auctioneer’s ear that one of the ladies feeling chilled had gone into the sitting room, collapsed and died.....”

• • •

“No doctor ever told me, but in browsing in the dictionary I have learned that I have Marasmus....”

• • •

“The old mare crashed through the glass and fell into the bed. There she lay, seemingly resigned and so trussed by her harness she couldn’t move. Mr. Hunter had never had a window display equal to this one....”

• • •

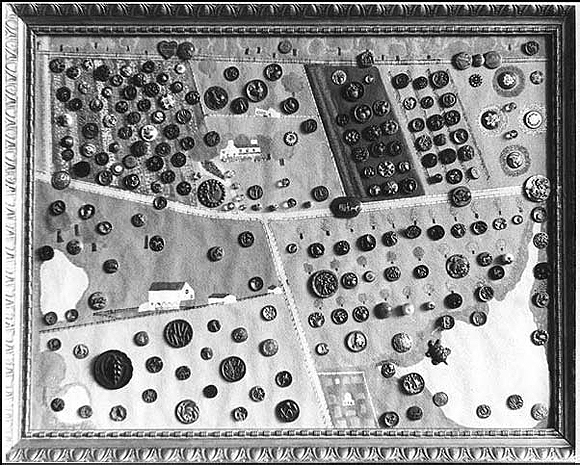

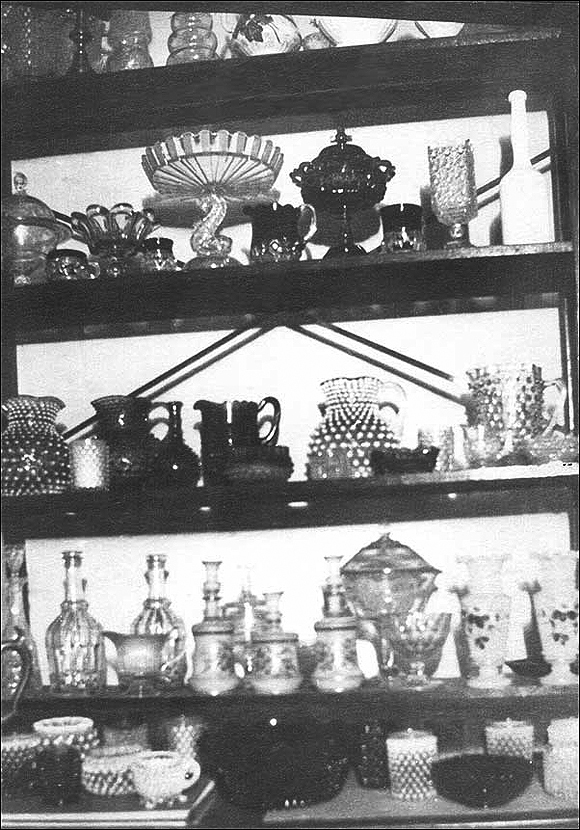

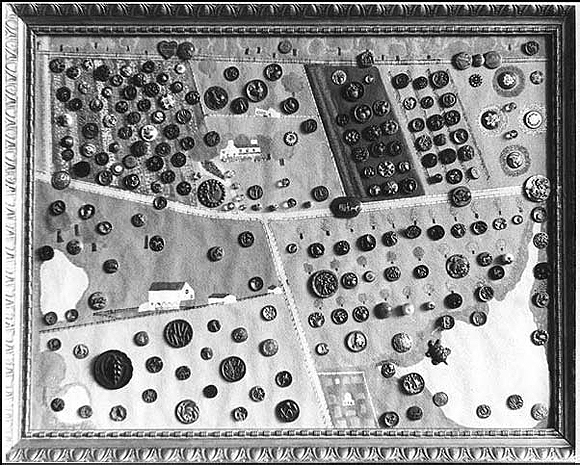

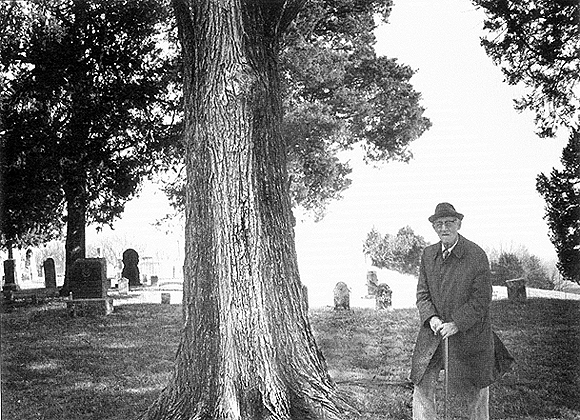

“As far as hobbies could carry me, I have ridden them most of my life. I have even changed horses in mid-stream. I collected stamps first, so long ago I have no recollection of what became of them. But I know I was thrilled to collect them. Then came postcards, photographs of pretty girl friends (this especially as a means to knowledge and aesthetic appreciation), bottles and jugs, pressed glass, flowers, lamps, old locks, brass door knobs, music, complete card-indexed records of every marked grave in my native Howard County, history, bustles, and now buttons. I wonder why I collect buttons?...“

Back Jacket

Dr. Warren Taylor Kingsbury

Scottsdale, Arizona

Despite having resided in seven states and worked in all fifty, Dr. Warren T. Kingsbury never severed his ties to Missouri’s Boonslick Community. He was born in Boonville, graduated from high school there, received an A.B. from Central Methodist College and Master’s from University of Missouri-Columbia. His Doctorate was earned at New York University. Dr. Kingsbury is now Professor Emeritus at Arizona State University.

A warm and close relationship with his uncle Lilburn Kingsbury developed in 1928 when Lilburn and Warren spent ten weeks helping valet 1200 Missouri mules on a tramp steamer to Oran, Algeria and Barcelona, Spain.

Through the years, they kept in touch by correspondence and visits. Dr. Kingsbury was enchanted by stories his uncle told of his many hobby horse rides, and he unsuccessfully tried to get Lilburn to write a book about them.

In 1983, Warren visited Lilburn shortly before his death. Lilburn asked Warren to review all of his papers, take those he wished, and arrange for others of historical interest to be given to the State of Missouri Historical Society. One of the things he said to Warren was “You always thought I should write a book about my hobbies. I was always too busy. Maybe you can find the time.” Finally, when he moved to Scottsdale, Arizona, at age 93, Dr. Kingsbury did.

HOBBY HORSE RIDER preserves many delightful hobby horse rides which contributed to Lilburn Kingsbury becoming a “living legend” well before his death.

Autobiographical excerpts from writings of Lilburn Adkin Kingsbury focusing on the hobbies he rode.

Copyright © 1998 by Warren Taylor Kingsbury

All rights reserved

The text of this publication, or any part thereof, may not be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, storage in an information retrieval system, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the copyrighy owner or the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review.

Editor: Warren Taylor Kingsbury

Publisher: Warren Taylor Vaughan, III

Editorial Assistant: Rosanne Lyles Armijo

Cover design: Rosanne Lyles Armijo

Copyediting/proofreading: Carol Kingsbury Weed, Warren Taylor Vaughan, Jr., M.D.

Printing: Walsworth Pub. Co., Marceline, MO

Typography/computer graphics: Thelma Green

Published by Timestream, Inc.

Oakland, California

info@timestream.com

www.timestream.com

Hardcover Edition (1998): ISBN 1-890709-01-8 (978-1-890709-01-3)

eBook Edition (2013): ISBN 978-1-890709-03-7

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number (Hardcover): 98-84382

Table of Contents

|

Hobby Horse Rider

Lilburn Adkin Kingsbury

Edited by Warren Taylor Kingsbury

|

Table of Contents

Chapter 1

Brother Billie Is Dead!

Idyllic existence of Taylor Kingsbury family is shattered by a shocking tragedy in 1932.

We have had an unbroken family circle for an unusually long time, but tragedy stalked in last night. Billie is gone.

His body, revolver clasped in his right hand, was found under a towering oak tree in Valhalla Cemetery in Overland Park near St. Louis.

His partner, Leo Meistrell’s, body was found in the locked vault of their offices. He had been shot once in the head, twice in the chest.

So wrote Lilburn Kingsbury to his Cousin Lillian Kingsbury Agnew in Great Falls, Montana on April 8, 1932. The letter continues:

Billie was taking Julia home about 7:25 p.m. She asked him to let her out of the car so she could go see Mrs. Nelson. Billie asked her how long she wanted to stay so he could come by for her on his way home from the office. She thought about ten o’clock. Billie said he would not be long. Julia had wanted to go with him but he told her she’d better not, as it might be cold up there.

Jere called me at six this morning asking that Horace and I come over immediately. We got there as quickly as possible. We learned Billie had not been seen since he left Julia, and his former partner, Leo Meistrell, was also missing. Mrs. Meistrell had talked to her husband at eight o’clock and had called again and had no reply. Julia had gone home earlier with Jere and had also called to tell Billie, but got no answer.

Mrs. Meistrell was quite frantic and so was Julia. The police were called out after midnight, combing country roads and searching for clues in the office and found Leo’s hat. Billie had gone up to open his mail, having been away a couple of days. The mail on his desk was unopened. I was in the office with several others and we rattled the vault door, but it never occurred to me it might hold a tragedy. The door was locked from the outside. Mrs. Meistrell and others thought someone should go to the cabin in the Ozarks so Jere and I with others made the 200-mile round trip in less than five hours, but when we got there to the store [at the bridge up the lake from the cabin] we found a message. Horace had phoned and said Leo had been found shot to death in the vault. Leo Meistrell was shot twice in the face and once in the chest, and had fallen on his face. The door was closed and locked.

We found no sign of Billie’s car at the lake nor anyone who had seen Billie, so we hurried back (to Boonville). By the time we got there, word had come from St. Louis that a body had been found in a cemetery at Overland Park, as No. 40 enters St. Louis, with a note pinned to it, asking that Mr. J.W. Jamison, a lifelong friend of Billie’s, could identify the body, and that H.M. Kingsbury be notified. Details were hard to get, but I think they said the body with two shots through it, had not long been there. Request was made in the note that the body be cremated. Horace, Ernest and two close friends of Billie’s have gone to St. Louis. None of the rest of the family will go. The remains or ashes will be returned to Boonville. I do not know what disposition will be made of them.

Mother and Father are bearing up bravely. We are all crushed, but we have been so fortunate through the years. I feel we can only accept this blow in a humble spirit or else be ungrateful for the blessings of the years. All of Billie’s children will be home as quickly as transportation can bring them. Julia is wonderfully brave. I think she has feared something like this for a long time.

April 9, 1932:

Dear Cousin Lillian,

An envelope addressed to Horace, mailed from St. Louis, came this morning. It enclosed a parking garage check for Billie’s car which Horace and the others had been unable to locate.

There was a short service at the crematory this morning at 11 o’clock attended by Horace, William, and a few close family friends.

It is still undecided just when burial services will be. If there is a service, it will be the Episcopal as Bill would like it, and Billie always thought that burial service was fitting. He didn’t care for music at funerals and there will be none. Service, if held, will be at our home. Julia feels she would like to place his ashes in Mount Pleasant, as the lot used to be a part of the farm which Billie always loved. No service before Monday. And then only for family and closest friends.

Father feels terrible and when I came to town a while ago he had gone to bed. We had tried to comfort him with the thought that Billie’s mental suffering is all over, but Dad says, “Mine isn’t.” We know the sympathy of the community is with us for sake of the parents if nothing else.

April 13, 1932:

Dear Cousin Lillian,

And the world goes on! The wheels of our mentalities have spun so fast lately it seems weeks must have elapsed. But we have nothing to do now except settle down to normalcy as much as possible and adjust ourselves to the living without dear old Billie.

Major Irvine was in St. Louis on business Monday and phoned he would bring Billie’s ashes as he returned that evening. I suppose you will be interested in every detail which I can think of to enumerate. I don’t know why it is so long before the ashes can be sent out after the service which precedes the cremation. They come in a rectangular copper box, 5 x 5 x 9. On one end was engraved the name and date, April 9, 1932. I don’t know whether that was to indicate the day of death or date of cremation. He died on the 8th. If it was in error, I kept it to myself, thinking nobody else noticed it. While it makes no difference, I always feel if a date is of any consequence at all in a case of this kind, it should be correct.

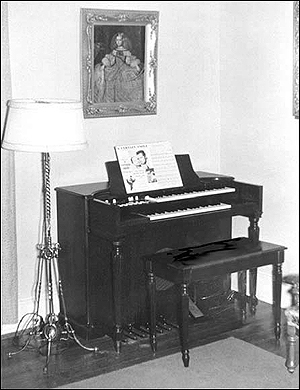

William placed the receptacle on top of the desk in the northeast corner of the parlor. There it reposed until yesterday afternoon. Some men and women who had just buried their mother that afternoon had brought in a large hydrangea with pink blossoms and this was placed on the desk also. On the back of the piano I had placed a large decoration of red buds with a few of the richest peach blossoms I ever saw, and it made that corner very attractive. Elsewhere in the house we used the spring garden flowers, narcissi and jonquils. We all live so close together we were in and out of the home constantly. Julia got so tired of seeing callers in Boonville that she found relief in coming over to our house.

Yesterday, all our family were present at noon. The sisters-in-law brought in and served lunch of ham sandwiches, fruit salad, watermelon and crabapple pickle, stuffed eggs, coffee, custard and cake. It was just the same kind of old family party except... Billie was absent. Not another person but family was present. We had all thought perhaps we wouldn’t feel like eating anything, but you know what good cooks the girls are, and the food was most tempting. It seemed a long afternoon when most of us were not able to sit down for long, nor could we find satisfaction in walking about. The whole family just shifted around from place to place in the house and yard except Father and Horace, who sat in the latter’s car and talked the whole time.

In the morning while I was downtown, Rosie and Margaret found Mother leaning over the little copper box crying her heart out and saying she just wanted to hold it in her lap. Of course, there was no reason why she shouldn’t and she did. It was a comfort to her. She heard Father coming into the house and told them to take it and put it back as she wouldn’t have him seeing her for anything. When the hour came to go over to the cemetery, she asked Horace if she could carry it over there and he told her “of course you can.” I knew Julia desired to do the same thing, and it was all planned she should. They told me to iron out the situation. I went in and heard Mother telling Father they were going to let her carry the box to the cemetery and asking him if he didn’t think that was nice of them. Mother was looking so pleased, I could hardly tell her Julia wanted to do the same thing, but I did and was pleased when Mother said, “Of course she should.” And after Julia and William got in the car to go, I carried the little box out and gave it to them and the procession started.

The lot to which the ashes were committed is right on the driveway, so they stopped the car with Mother and Father in it immediately beside the spot. Father wanted to get out, but finally was persuaded to stay inside.

The place prepared for the box was simply the base upon which will be placed a modest marker. A space for the box was prepared inside the base and a blanket of pink roses, pinkish brown snapdragons and different shaded pyrethus, not very large, perhaps four feet by three, was spread out over it. As the undertaker advanced with his little box, his assistant folded back a part of the flowers so the ashes could be put in place. The flowers fell back in place, and Rev. Gregg used the shortest service he knew. He delivered it very eloquently and I liked it very much.

In spite of the fact it was a private service, there were a great many people and we were glad to have them, or anyone who felt really impelled by love for Billie to come. Julia had said she wanted just his immediate friends and I told her that would include quite a large circle, for there were people who were his friends of whom we knew little. We have learned as the days have passed, people have said Billie had done this or that for them.

Everybody came back to the house, but all of Julia’s family returned to Boonville late in the afternoon. I think all of the others stayed for supper and dwindled away gradually until nine o’clock when we went to bed feeling like we had been beaten over the shoulders with a club.

Mother said this morning she and Father felt more reconciled, and I believe all of us are going to be able to get up before the “count of ten” and fight the second round. For a lot of us this is the first round with sorrow we have had.

A safety box, with the name Kingsbury and Meistrel on it was found under the bed in a room at a motel on Highway 66, 30 miles west of Kirkwood, a suburb of St. Louis. Sheriff Groom and a young attorney named Martin went down to recover it. They found it empty except for three documents which were under a secret flap, and in the stove in the room there were charred remains of papers, a few unburned edges indicating the papers were of a legal nature.

From Jefferson City, Billie had mailed a dollar bill to a girl friend of Julia’s, who had done some stenographic work for him in Boonville a few days previous. He was fond of her and she of him and she was just crushed to have received it from him in that way. He mailed some sort of paper to Albert Smith [a cousin] and a purse containing some money to Judge Fisher, Leo’s father-in-law. This was money which belonged to the Meistrell children from sales of the Saturday Evening Post. No doubt Leo had pitched it in the box and Billie found it and returned it. Presumably everything in the box was burned except the three concealed items. Obviously, Billie felt Leo had cheated him and would proceed to cheat others who had dealt with them as partners.

Surely something must have arisen of great provocation to Billie. There had been a failure on Leo’s part to live up to the agreement of last August to care for certain obligations he was assuming. Such a lot we don’t know and can’t understand, but Billie was a fine man. I have always been proud of him and I am proud of him yet. Think what a man he was to have the courage to go through with his suicide after all these hours following Leo’s removal from this planet.

Stops in Jefferson City to go through Leo’s deposit box and return certain things, doubtless a sorting of the papers at the motel, where he arrived at 1 a.m. and remained until 7 a.m. He arrived at the St. Louis downtown garage, where he parked the car at six after ten, got the check for it and mailed it back to Horace, then took a street car, from which he had to transfer to the Wellston Line leading to Valhalla, and the remainder of the time was consumed in the ride to that destination. At the Boonville filling station where he had his car serviced, at the motel near St. Louis, and at the garage, the attendants noted nothing a bit unusual about him. I can almost see him dropping off the car at the Valhalla entrance and walking briskly along to the great sycamore tree under which he passed into the great unknown, about 200 feet from the gate.

I wonder if Billie didn’t have the old Viking legends in mind when he planned all this avenging destruction by fire and entrance to Valhalla.

When he was missing last Friday morning, Mother cried and prayed he might be spared the sufferings which would be involved if he was apprehended. He did not finish the job any too soon, for people would have begun to look for him as soon as the broadcast of nine o’clock became generally known. And by the time he was leaving the car at the garage, requests for his arrest were being radioed.

Well, he was a sweet old thing, and we shall miss him; but if he were terribly unhappy in this life, perhaps it is well it is all over...

I wouldn’t feel free to send this sort of detailed letter to anyone except the dearest to us. I felt the exhibitions of mother love were almost too sacred to mention, but you are such an understanding person.

This was Billie’s note:

“Have no regrets except for family - all of whom I love dearly. This is the first time my mind has been clear for months. I could feel myself slipping and I do not care to be a drooling lunatic on my family’s hands regardless of their affection for me.

“Julia certainly deserved better than this for she was all that could be asked of a wife and more. If I had only listened to her, Leo would never have had a chance to put me where he did. So I square my account with him and take mine. I thought he was afraid to cheat me. I was wrong. He thought I was afraid to kill him. He was wrong.

“Am not writing Julia or any of the children. There is nothing to say which could do any good and I can’t say I would not do it again under the same conditions. Will mail receipt for car which is to go to Jere, with his mother’s consent.”

Table of Contents

|

Hobby Horse Rider

Lilburn Adkin Kingsbury

Edited by Warren Taylor Kingsbury

|

Table of Contents

Chapter 2

Your Golden Years I'll Spend With You

Celebrate Golden Wedding Anniversary • After the party was over • Genesis of letter-writing hobby • Getting the old furniture bug • Not born to pull bolts of goods from shelves • Establishing an office • A golden year gallop.

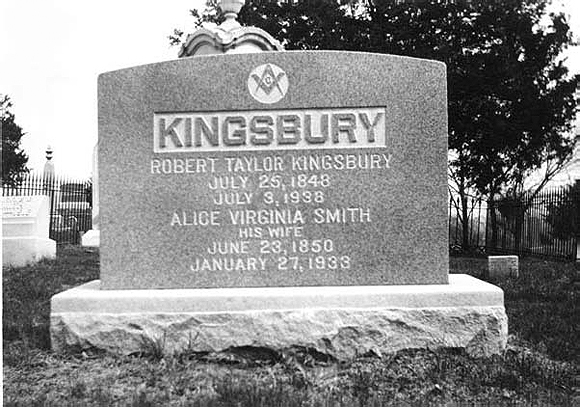

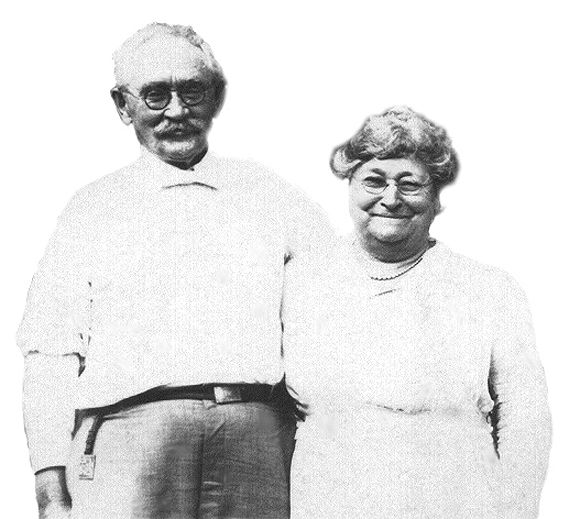

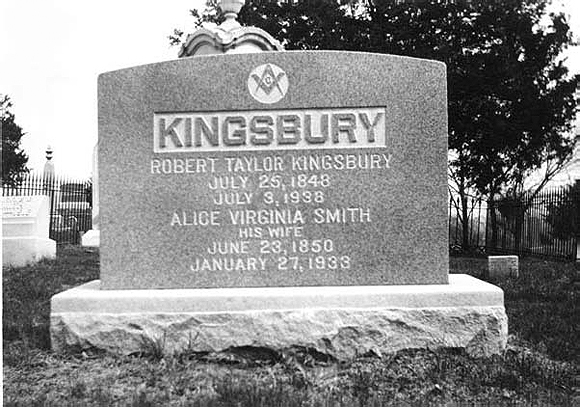

On the day of their wedding, April 21, 1872, Taylor Kingsbury carried his bride, Alice Virginia Smith, across the threshold of Fairview, the comfortable big home built by slaves in 1833. The place was a wedding present from his father, Dr. Horace Kingsbury. Soon after, Taylor planted the first commercial apple orchard in Missouri. All seven of their children were born there. Throughout their 50 years of marriage, Fairview had been a happy home free from tragedy and crisis, filled with joyous memories of their growing family, friends and relatives who frequently gathered to celebrate holidays and special occasions.

Fairview was a mile north of New Franklin, the shopping center for those farming the rich Boonslick Country heartland. The town of about 1600 was on a rising slope up from the Missouri River about three miles away. Looking south across the bottom land and the river, one could see Boonville, a town of about 4500 stimulated by riverboat traffic. To get there, one crossed the river by ferry or rode the Missouri, Kansas and Texas Railroad.

Lilburn was then 38. He usually walked a mile south into New Franklin where he was cashier and manager of the Bank of New Franklin. He also had an insurance agency and was active in church and community affairs. A personable, interesting bachelor, he never lacked attractive feminine companionship.

Bank work was keeping him busy. The directors decided to build a new bank building. This and responsibility assumed for promoting and making loans and attracting new depositors ignited his interest in banking.

He spent less time at Fairview. When he told his parents the demands of his work might better be met if he moved to town, it brought a tearful session with his mother. She tearfully lamented, “All your brothers and sisters have gone off and left us. And now you’re going to desert us and we’ll be all alone in this big house. What will we do?” This so moved Lilburn he vowed he would never abandon them. Their well-being was much on his mind - something needed to be discussed with his siblings after the golden wedding party was over.

On March 7, 1922 Lilburn wrote his Cousin Lillian Kingsbury Agnew of Great Falls, Montana, alerting her and numerous Montana relatives of the golden wedding celebration being planned for his parents.

Prior to taking major responsibility for planning the golden wedding party, Lilburn, although a loving son, respecting and honoring his parents, had lived a rather fancy-free existence. Both parents idolized him and gave him the run of their comfortable, pleasant home. He had given little thought to the mortality of his parents, taking their continued presence at Fairview as a given.

A golden wedding celebration was indeed a special occasion! Lilburn, the only unmarried child, living at home, undertook to see it was.

“Father and Mother are going to have a big party on April 21 to celebrate their golden anniversary, and I hereby extend all of you an invitation to come in for the event, and all accompanying activities. We have not decided on the nature of the affair, except it will be quite a public affair, with everybody invited and no presents. We will have to get our heads together from now on to get all the plans made and effected by that time.”

All the children and grandchildren, many relatives and friends were present. One of Grandfather’s brothers, Adkins, a prominent Montana rancher who was later honored by being named one of the state’s two representatives in the National Cowboy Hall of Fame, and his daughter, Mary, came out for the event.

On May 9, 1922, Lilburn wrote his Cousin Lillian:

“I am sending you a newspaper account of the golden wedding. I have intended doing this sooner, but not until today did I get down to the office for the papers.Ever since Uncle [Adkins Kingsbury] and Mary and Anna Rose and the others came, I have been going, stretched out, on the gay, good-time race track. We haven’t had a nickel’s worth of sleep. I am exhausted, but hope to recuperate in a day or so by getting a few nights’ sound sleep. There hasn’t been anything special to do here, but always some place for us young’uns to go and get home late.”

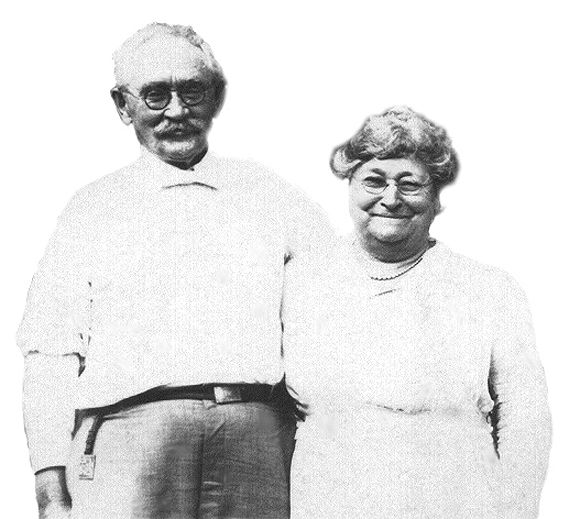

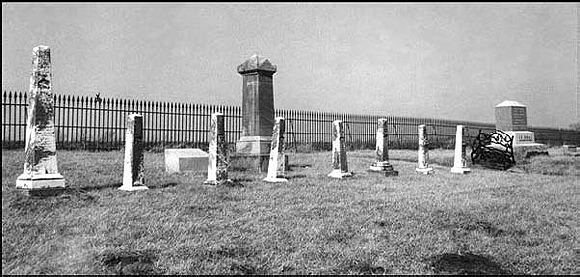

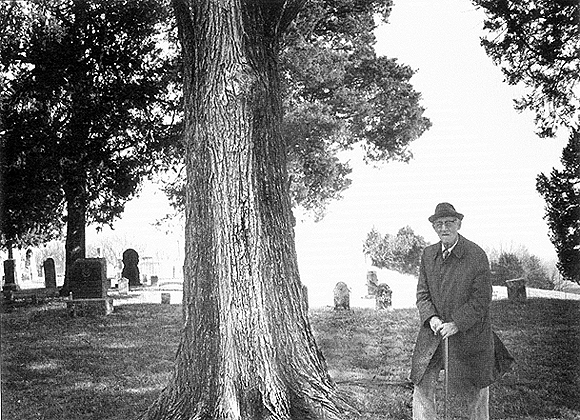

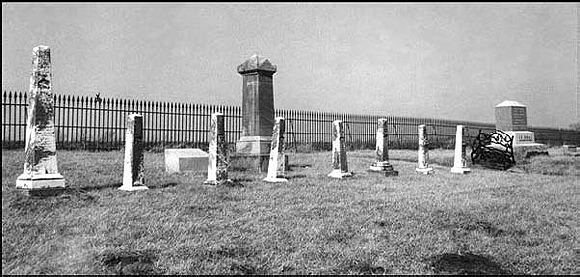

Robert Taylor and Alice Kingsbury at their 50th Wedding Anniversary

New Franklin News - April 30, 1922:

A day so fair that even fairies could not complain of the loveliness; an old gray brick home surrounded by budding maples; a flowering orchard of pink and white blossoms to the south; waving fields of young wheat and grass to the west, and the old cemetery to the east, added a touch of sacredness and holiness to the occasion - that was the picture one looked upon as they drove to the home of Mr. and Mrs. R.T. Kingsbury last Friday afternoon to participate in the Golden Wedding Anniversary celebration of this highly-respected couple of southern Howard County.

Nothing could have brought more happiness to friends and relatives than that day. Fifty years of wedded life, not all sunshine, but so much happiness that it made each one glad to press the hands and kiss the lips of these good people, who along the downward path never failed to help the less fortunate, and who have always lived near their God and found all things well. They are now looking toward the sunset of life, their cares are behind them, but by their presence, true reflections of upright Christian characters, they have helped make the community a better place in which to live.

The old house on this day was at its loveliest. The spacious old rooms with their soft light, abundance of cut flowers, the dining room table (the most attractive of all) with the large wedding cake surrounded by 50 lighted candles, the mingling together of the sons, daughters, grandchildren, relatives and many friends of the bride and groom of 50 years was an occasion long to be remembered.

Mr. and Mrs. Kingsbury are lifelong residents of southern Howard County, their birth places being only a few miles from their present home. They have seven children, five boys and two daughters, all of whom returned to the ‘old nest’ for this most joyous occasion. They have every right to be justly proud of these children.

Horace M., the eldest, is one of the best known and successful (now retired) farmers of Howard County.

The second son, William Wallace, has long been a prominent banker and influential citizen of Boonville.

Ernest, the third son, is a prominent and well-to-do citizen of Omaha, Nebraska.

Robert, the fourth son, is a prominent farmer and fruit-grower, his farm adjoining the home place; while Lilburn, the youngest son, is one of our bankers who has played an important role in modernizing banking business in this city.

The oldest daughter, Lillian, is the wife of C.A. Edmonston of New Franklin, and is socially prominent in community activities.

The baby of the family, Anna Rose, is the wife of Will Darneal, a successful businessman in Richmond, Missouri.

About 200 guests were assembled for the occasion and the program was very informal, just as Mr. and Mrs. Kingsbury wanted it to be. The afternoon was spent in social communion, and the renewing of old acquaintances, intermingled with many musical selections rendered by the Culley Orchestra of Boonville. Delicious refreshments were served from the dining room throughout the afternoon.

We congratulate them upon having attained the coveted station in holy wedlock, so often viewed from afar, but so seldom realized. With their present good health, the family chain still unbroken, and bright prospects for many more happy years, they indeed have much for which to be thankful. Their lot is an exception and would it be out of place for us to say, that payment for work well done and faithful servants, has begun on this, the earthly kingdom, while most of us have hopes only in the great beyond.”

Lilburn’s letter continues . . .

As a hearty eating Kingsbury, I’m sure you wish to know about the refreshments.

We served white brick ice cream with yellow heart in the center - heart of apricot ice - individual cakes iced with yellow icing flavored with orange peel. We engaged a five-piece orchestra with a woman singer. While they are a regular jazz orchestra, besides a lot of jazz, I had them play “Kiss Me Again,” “Oh Promise Me,” “Mother MaCree,” and things like that. The vocalist sang the old song about Maggie, “Silver Threads Among the Gold,” “Carry Me Back,” etc.

We had no ceremony - no eulogizing remarks from anybody. It was just sort of an “open house.”

After the Party was Over

It was not long after house guests departed that life at Fairview resumed its normal living patterns. But soon Alice and Taylor’s children and their spouses began discussing how best to assure their elders might live out their lives comfortably in their beloved home.

Discussions culminated in agreement that:

1. Lilburn would continue living at Fairview.

2. Lilburn would assume responsibility for supervisory management of the orchard/farm.

3. Lilburn would monitor his parents’ well-being and provide for their needs - using income from the orchard/farm for that purpose and any improvements in the property he thought necessary.

4. In return, siblings and spouses agreed to waive any claim upon the property.

5. At the death of both Alice and Taylor, Fairview would become Lilburn’s “free and clear.”

To Carry Out This Agreement:

1. He had to find and keep a watchful eye on “live-in-help” to do most of the cooking and cleaning.

2. Employ a farmer to live in the tenant cottage and work with the other farm hands.

3. Begin refurbishing the house and grounds so they would be what he wished when the property became his.

Genesis of Letter-writing Hobby

With these responsibilities added to the growing pressures of his banking, insurance and church obligations he continued writing to relatives. In a Lilburn Says column written in 1972 for the Boonville Daily News, he gives the genesis of this hobby:

For more than 80 years my palm has itched to write and receive letters. Scratching it has afforded me immeasurable pleasure.

It began during the romantic days of high school. A young girl classmate and I, though we had never dated, had come to an agreement that we would pretend we were Lord and Lady Earl of English royalty. Of course, there were official edicts I had to communicate to my lady which had to be delivered during school sessions by couriers in seats which separated us. The thrill of doing this was increased by the risk of having our messages intercepted by the teacher.

In 1901, it was no bother for me to walk a mile daily to and from Estill, our post office, to get a letter from and mail one to the prettiest girl in the world who had visited in New Franklin, but now lived 150 cruel miles from me. Old Mr. Grider, clerk in the Tutt store where the post office was in the back corner, used to welcome me at the door to gladden or sadden me - “It’s here” or “She done forgot you today.” . . .

He goes on to tell of fascinating female correspondents developed in London, Paris and across the United States. He concludes:

“If I ever fail to get letters, I think I shall die.”

Lilburn knew, to get letters, he had to write letters. This he did diligently - especially in these years to his Cousin Lillian Agnew. In them, he tells of some new hobby-horses he had saddled, bridled and on which he had galloped away.

One of the first things Lilburn did was to get live-in help. This resulted in employment of Mary Kuhne, a deaf mute woman of about 30. Lilburn wrote of her to his Cousin Lillian as follows:

Mother and Father have been pretty well since the first of the year except for colds. Our girl hired as live-in cook and maid gets better all the time and Mother often laughs after breakfast and says, “She has such a hard day ahead of her.” Then Father giggles and says he has too. They spend the day reading, sewing, and picking out nuts, sleeping and just having a good time resting.

Mary Kuhne keeps the house well and Mother has taught her to enunciate quite a number of words. I am sure if one devoted a lot of time to Mary she could be made to speak. She is devoted to Mother and whenever she writes to know anything about Father, calls him “Papa.” We feel like we have a jewel.

Lilburn paid increasing attention to making Fairview what he visioned it being when it became his. He quickly began redecorating the place and replacing the furniture with early American antiques. Collecting these antiques was just becoming fashionable in Boonslick Country. Most of the beds, tables, chairs and chests which had been brought from Virginia or Kentucky, or crafted by the skilled woodworkers emigrating into the community, had been sold off years before or given to the Negro help. Much of it at the time was adorning their shanties. Lilburn wrote Lillian Agnew about the new hobby-horse he was riding.

Getting the Old Furniture Bug

I don’t believe I have written about getting the old furniture bug. I used to laugh at Henry Tindall [a cousin living in Fayette] and Sister Julia and everybody else who cared for the old stuff, but one day I bought a piece of it, got varnish remover, and reduced the wood to its natural finish, then refinished it with satin finish and it looked so good, I decided to furnish a room.

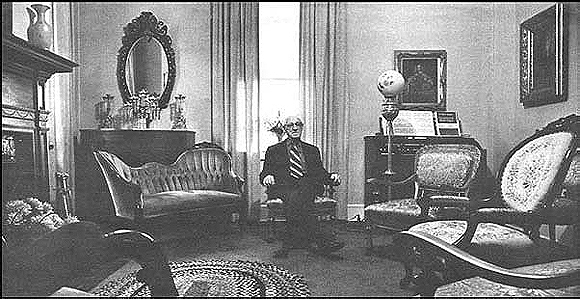

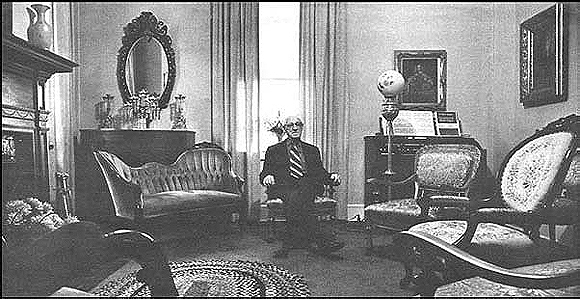

Lilburn in his Fairview parlor with some of his antique furniture

I found a double and a single Jenny Lind bed, both beauties which I had a professional workman finish. Then I traded for the pieces of another one and used the turned pieces and the spindles in having a table and window bench made. I cut up more of the spindles and used them to ornament the top and bottom of a screen made of walnut panels. Then old Mr. Furniture Man gave me a foot-stool, and I picked up some attractive old chairs, all the little stuff, and an old dresser which I found in Moberly at a second-hand store. The little table I had made has a pedestal which came from wood out of our house when we remodeled. The spindles are from a bed brought from Virginia and the top came from the shelf in Grandfather Kingsbury’s old desk. I have found some attractive old picture frames in which I have put prints from old-fashioned pictures. You must have surmised by now that my “stuff” must have over-flowed into another room. My prize piece is a chest of drawers about 85 years old, of cherry and walnut with ash veneer trimming and glass knobs which I found in Warren County, at the home of a spinster, with whom I have been corresponding in the hope of purchasing more of her things.

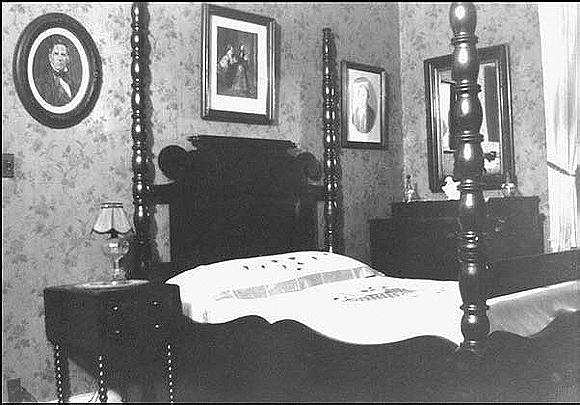

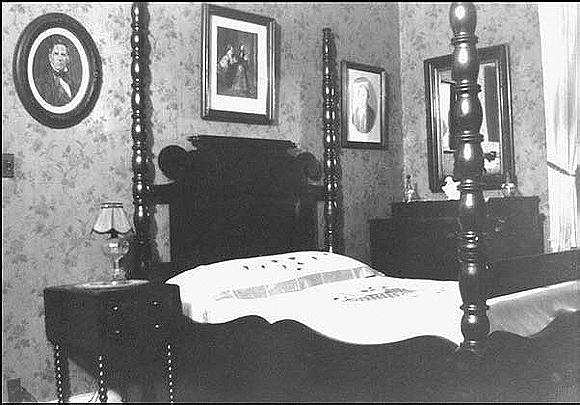

A bedroom in Fairview, the Kingsbury home in New Franklin, Missouri

Pretty soon I will have the house done over to match the period in which it was built, providing Mother does not pitch me and some of my old stuff, out into the yard. I have had an electric light made using old-fashioned prisms, and also two tall brass candle-sticks which have been adorned with a collar of brass from which to suspend prisms. These are especially attractive. That is how I have spent a good many evenings since the new year. The second room I have started to fix up is to have burnt orange and black draperies and trimmings and will be real gay, festive and loud. After I get these rooms fitted up, I will call them “The Trap,” for with them, maybe I can catch a girl. . . .

I’ll try to keep you posted on how we’re progressing. This year we thought of putting down hardwood - but it is so expensive. I decided I’d see what kind of floor we had down under the paint. So one rainy day, I didn’t go to the bank, but got lye and went to work on the front hall. It’s about 20 x 6 and I found it a terrible job. Took me about eight hours and by then I didn’t have any legs or back left for comfort. The floors in this house are of ash and such a pretty grain. I’ve just put a coat of shellac on the hall floor tonight, and when it dries, it’ll be ready to wax.

In mid-summer, he wrote his cousin:

It’s been about all I can do, moving things along at home, and looking after a bank, but just lately my date and I have been going swimming some and progueing around at night. This I enjoy and at such times I forget my age and responsibilities.

We had a wonderful drive Sunday evening across the hills to Boonsboro, then on to Lisbon, arriving there just about sunset. Then we came back along the bluffs and watched the sunset reflection in the river. We watched the bright colors fade and the stars come out. And the whippoorwills calling and the frogs singing and the high water splashing against the rocks below, and millions of fireflies lighting the cliffs and woods above us. It was like a dream spot, and we stayed so late, we surely had to “whip up” to get home by midnight. We wished for a stop-watch so we could have more time. Now that sounds like serious doings, but coming from me, just pass on over it. I never heard wedding bells ringing up there on the river. But to me, it is the most beautiful spot in the country and I enjoy it as does anybody else with a love of nature. It was so nice Sunday evening I have asked the same girl to go back there with me.

As manager of the bank, Lilburn found himself faced with foreclosing on the Clark Store whose terminally ill owner could no longer manage. Lilburn’s store-owning brother-in-law assured Lilburn it could become a successful operation. So, in addition to his other banking responsibilities, insurance business and supervision of the orchard/farm, Lilburn found himself running the store.

Public response to his management was so ego-satisfying that he bought it from the bank and gave it the Kingsbury name. He thought this might provide the escape from the bank he was seeking.

It took little more than a year for his ego to be fully satiated with store involvement. He felt fenced in, unable to find time to ride his hobbies.

Not Born to Pull Bolts of Goods from Shelves

The New Franklin News of September 26, 1924 announced:

“Mr. Kingsbury is closing out his store because of other interests which require his entire time.”

That wasn’t the whole truth, Lilburn told me late in life when I asked him about his experience as a merchant. He said he always had interests to which he wished to devote his entire time but that he soon found the store wasn’t one of them. He went on to say:

I discovered I had not been born to the art of pulling bolts of cloth from shelves for discriminating women and then putting them back in place only to have to repeat the performance for another customer.

I couldn’t become accustomed to seeing the latest styles of ladies fashionably trimmed hats tried on by women who punished them by pulling a brim up or down trying to make it attractive to their faces. I grew weary of women trying on dress after dress and more often than not leaving the store without buying a thing or even saying, “Thank You.”

The News story continued:

The entire stock of the Kingsbury Store will be placed on sale in a Quit Business Sale. It is arousing county-wide attention and will no doubt attract people by the hundreds. The people of South Howard County particularly know the goods are fresh stocks offering bargains seldom found in a close out sale.

...Besides the usual and far-reaching reductions ample in themselves to attract hundreds of shoppers, a contest will be inaugurated and many valuable prizes will be awarded during the sale. New stunts will be introduced every few days that will be of great interest. Mr. Kingsbury says this is positively a quit business sale and the big selling event will continue until everything is disposed of.

The following week’s News (October 3, 1924) carried this story:

The Quit Business Sale of the Kingsbury store continues to be the talk of the Town and Country and the store is filled daily with eager shoppers.

Interest is kept at fever heat by the new and unusual stunts concluding with the giving of some useful, worthwhile prizes. Contestants working in the sale for the 10 capital prizes offered by the store at the conclusion of the sale are all distinguishing themselves as hard workers seeking patronage for the store with the hope of securing votes to win some worthwhile prize.

Wednesday, October 1 was registration day and a great day for the Rustlers, as the contestants were called. Every person registering at the store had 1000 votes to give one of the contestants and every mile one came (up to 30 miles) in order to register, counted another 1000 votes. People were registering from New York, West Virginia, Colorado, Michigan, Kansas, Indiana, Illinois and Iowa. The Rustlers were even waylaying tourists passing through.

The end of the sale was reported on October 17, 1924:

The Kingsbury Quit Business Sale closed at 3 o’clock this afternoon, every article in the big stock of ladies wear, dry good and gents furnishings having been sold.

The sale in many respects was the most unique ever held in this section of the country. What contributed more than anything to the complete success of the sale was the interest in buying caused by the Rustlers’ Club who were competing for the 10 capital prizes. [First prize was a diamond ring; second, a handsome cedar chest.]

Of all the stunts, the most interesting was the giving away of the “real live white baby” on Wednesday of this week. It was the talk of the town and at 9:30 of that evening the store and street were blocked with people eager to see the baby and the winner. The doubt among some and curiosity among others as to whether or not a real baby would be given away only added to the interest and the award offered much amusement.

The baby proved to be a small white pig all dressed up in baby clothes and was won by Mrs. Margaret Robinson.

With the closing today of its doors, the Kingsbury Store passed out of existence in this city, a fact much regretted by the many friends of the store throughout the Boonslick Country.

When Lilburn and I were discussing his store, I asked him if he had any regrets about closing it. He closed his eyes, pressed the palms of his hands to his cheeks, and was silent, apparently in deep reflection. Then he opened his eyes, dropped his hands, looked roguishly at me, grinned and said,

“Well, yes. I wish now, I’d promised to give away ‘two real live babies - one white pig - one black - but that was before desegregation.”

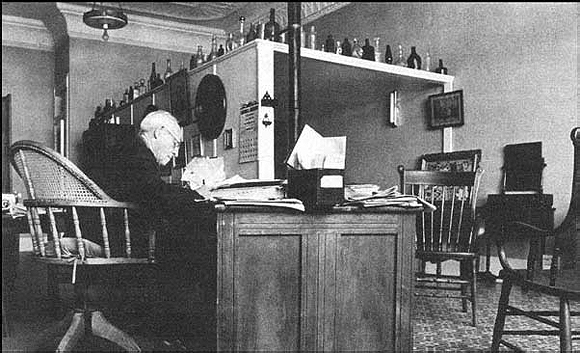

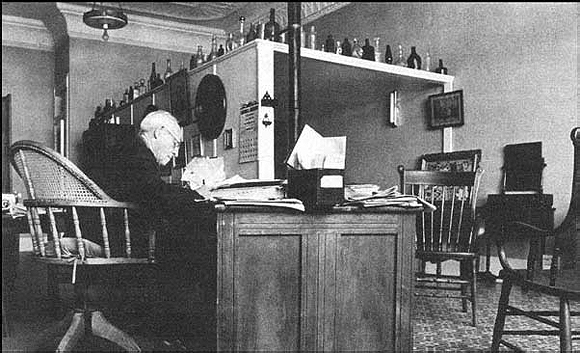

Establishing an Office

Shortly afterwards, to devote more time to his parents and orchard/farm operations, Lilburn left the bank. He bought the building across the street vacated by the Citizens’ Bank when it merged with the Bank of New Franklin. There, he established an office he maintained until his death in 1983. From it, he serviced his insurance customers, handled the Fairview records, stored many of his collectibles, and kept his genealogical and historical records. Unless he was away on a trip, he tried each day to spend some time in his office.

These two moves enabled him to fulfill the commitment made to his brothers and sisters of looking after the well-being of their parents.

On October 3, 1925 Lilburn wrote Lillian Agnew about this:

The hot days of September played havoc with the Jonathan and other fall apples, preventing them from coloring and they nearly all fell off onto the ground. The winter varieties are falling so badly we are having a terrible waste in harvesting the crop...

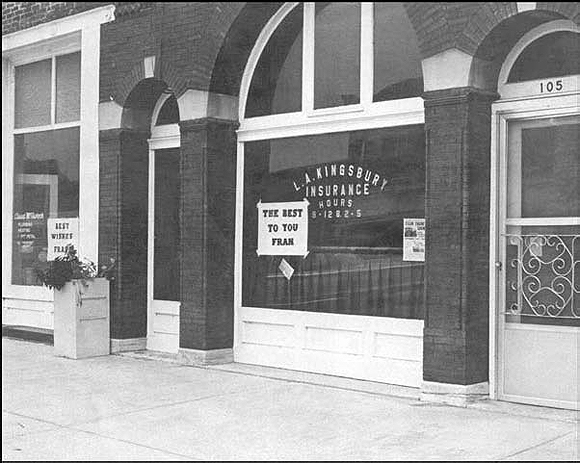

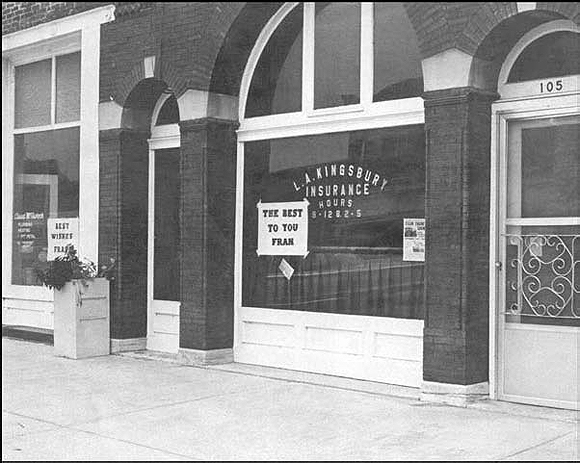

Lilburn's office in New Franklin

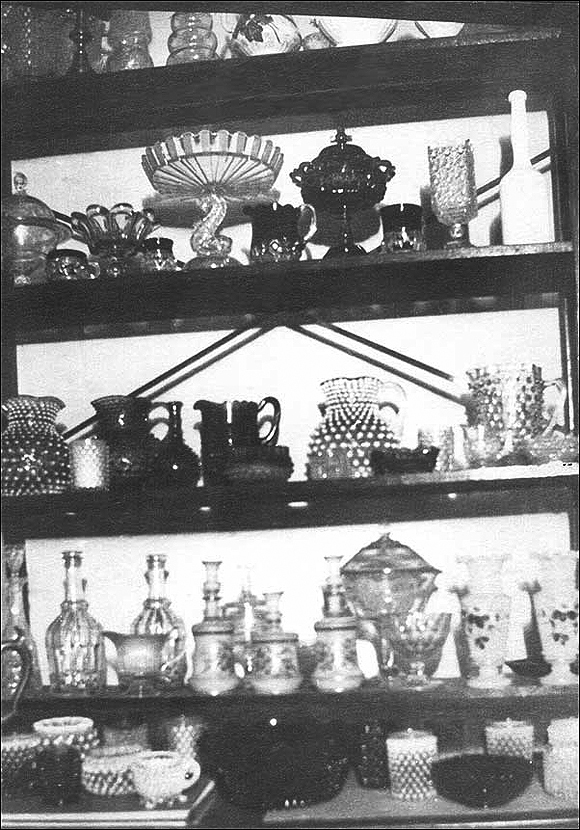

I am still antiquing around. These last few weeks, I have added a mahogany table, a mahogany dresser, and the quaintest old brass lamp you can imagine to my collection. Am having the old lamp wired for electricity so its appearance will not be changed. The mahogany furniture has such lovely crochet designs on it. Then I had some foot-stools made, but instead of a cross-stitch top, I am using a hooked woolen top.”

Paralleling Lilburn’s interest in furnishing Fairview’s interior with antique furniture, glass and china was a desire to embellish the surroundings of the old home. In the text of a talk he gave in 1977 to a Boonville Garden Club, he wrote:

There was a time, 45 years ago, when I was just as enthusiastic and devout a gardener as you are. I was making a formal garden (60 x 20) at one side of my house. There was a large bed in the center with rock walks from three sides to and around it. The walks were bordered with jonquils. As much as possible, I planted perennial flowers: lilies, delphinium, poppies, gaillardia, hollyhocks and iris. Highly esteemed were the “starts” which garden-minded friends gave me to “homestead” a claim on my garden. It was beautiful in its formality for many years - but how informal it is now!

In 1925, the road past my home was christened No. 5 and a concrete road was built. To widen it, they cut off a part of our front yard. They left a terrace across the front, a deep bare surface which seemed unsightly. I conceived the idea of planting iris on that terrace to spell out the name “Kingsbury” using a different variety for each letter, arranging them as much as possible so the colors would harmonize.

It made a beautiful display for years, and people had no trouble finding where the Kingsburys lived.

A Golden Year Gallop

The winter of ’26 - ’27 was a severe one. Lilburn’s parents had resisted Lilburn’s attempts to persuade them to go to Florida, where they might get out and around. Spring brightened their lives. Their health improved. They became restless and “put their goin’ shoes on.” With Lilburn as the chauffeur and his sister Lillian along for the ride, off they went. Lilburn wrote of their “wild ride” to his Cousin Lillian on July 20, 1927.

We have been back home 10 days from that wild ride through Missouri and Arkansas. Toward the last days it became a hurried and distressing trip, but now that all of the wrinkles put in us have been ironed out, we are inclined to renege on our oath that we would never go again, and have even expressed the hope we may yet get to Niagara Falls. In Memphis, mother said she could not eat fresh peaches, for they always “just ruined her.” But not many hours later, when I brought some fresh peaches to our room at the hotel, she proceeded to eat two of them. When we got started on our way in the afternoon, she was seized with awful griping.

We were carrying a bottle of Chamberlain’s Colic Cure with us and I gave her the prescribed dose for an adult. It was good for her in a way, but she declared I had given her too much, for her stomach burned so badly, she continued to feel quite miserable. We were headed for Sikeston, Missouri, 157 miles and we had a good trip, but ran into a wind and rain storm which worried mother terribly. We pressed on to Sikeston where we intended to rest a day or two and give her a chance to recuperate.

But we were not destined to remain in Sikeston long. We arrived at 8 p.m. and at 6 a.m. mother was up, as was father, and was clamoring to ride on so she could get home as quickly as possible. She looked just awful and was so hot we all knew she had fever, but she wouldn’t listen to reason, and we thought it might make matters worse to use force, so away we went, rushing to get the 155 miles to St. Louis in time for her and father to catch a train which would get them home a little quicker than we could drive the distance. Mother was complaining of such pain, we figured a Pullman would be much easier on her. By the time we arrived in St. Louis, I knew she was in no condition to go on a train or anything else, so we just went to a hotel and remained until she was better. The following day, after a good rain in the night, we had a lovely cool day and availed ourselves of it to drive on home and she stood the trip nicely and has been resting and improving ever since.

Father was like castor oil to the rest of us. We would not get to bed at one place before he would have us passing on to the next. Always up by seven and ready for me to drive the car around and load up. And if we made our allotted daily distance in good time he would see no reason why we could not go on to the next big town, 60 or 70 miles further, provided the roads were reported good.

When we got to Hot Springs, the rest of us just struck on him and said we were settled for at least three days, when he said just after we got up to our rooms, “Well, I have seen all of Hot Springs I care to see for a while.”

The rest of us enjoyed everything there and have decided it would be a nice place to spend time in the winter, the busy season. It is a town with a permanent population of 16,000 which has accommodation for 25,000 visitors. It had one long crooked main street, and the $12 million worth of bath houses are all in a row on same. There are foreign shops like one sees in Los Angeles and San Francisco, and hotels and cafes by the hundreds. We liked the water very much. There are some 50 springs but the mineral content of the water varies so little in any of them that the difference is negligible. Some of the water is 172 degrees hot, and is drinkable though too hot to hold your hand in.

Our next stopping place of any importance was Memphis, though we did spend a night in Morrillton and went out to see the nurse who had taken such good care of father in the Boonville Hospital. There we found three of the old Boonville nurses and they chatted and took on over dad and seemed very glad to see us. They had gone down there to open up a hospital. We were located so nicely in Memphis that I was hopeful father would catch the like-it from me.

Before we had enough of Memphis, dad decreed we should move on. Next time he wants to take a trip, we shall get him connected with some passing band of gypsies. He thrived on the trip, apparently has regained his customary weight and looks fine. I think he could have gone on indefinitely, provided we did not stop anywhere long. But since he has been home, he has complained of some abrupt shortness of breath when he exercises. This is probably due to excessively high temperatures, as our weather has been pretty warm.

Since I have been home, there has been the hay harvest and plenty of other things to do, some of which are done; some are not.

Table of Contents

|

Hobby Horse Rider

Lilburn Adkin Kingsbury

Edited by Warren Taylor Kingsbury

|

Table of Contents

Chapter 3

Stubborn as a Mule

After the mules came Italy • Into a hurricane • From mules back to hobby horses.

In 1928 Missouri was known as the Mule Capital of the world. It was estimated the mule population was more than 500,000. The state’s rugged mules were stubborn and in demand by the Spanish Army and the French Foreign Legion. The Barnet Mule company in East St. Louis did a thriving business of buying mules and selling them to those military bodies. They made five or six trips a year to Europe. The mules required care-takers. It became “the thing” for recent college graduates to sign on to tend mules on the long trip across the Atlantic.

My college roommate, Roy Basler and I, were planning career changes in June when we heard about a trip starting from East St. Louis on July 1. The following weekend we were at my parent’s home in Boonville talking with Lilburn, who was a visitor. Things were going well at Fairview. The live-in-housekeeper/cook was seeing to his parents’ needs. Neither was experiencing serious health problems. The farm foreman was experienced and competent. Lilburn’s office secretary could look after his insurance business. Our excitement about the trip was contagious. Lilburn caught our enthusiasm and called Barnet. They were delighted to have him because of his experience working with mules.

Lilburn was then 43 years of age. He was not a handsome man but had an engaging personality. He was about six feet tall with reddish- brown wavy hair. He looked directly at you with bright, blue eyes. His friendly smile reached out and drew you to him. His handclasp was firm and dry. He spoke with a bit of a drawl that aroused interest and held attention. Physically, he was in excellent shape. The farmwork he did was enough to keep his muscles firm and his body trim. Perhaps the following excerpts from an unpublished Lilburn manuscript, based on the diary he kept will enlighten you as to just how stubborn a mule can be! Today (1998) you’ll probably be unable to find one in the once “Mule Capital.”

Three dozen young men were hired to tend the mules on the 21-day trip from Norfolk to Barcelona. I was the oldest of the group. Most were recent college graduates and had never done a day’s work at hard labor in their lives. But they were lured by the promise of free transportation and $1 per day on the outbound voyage. They were yearning for adventure on the ocean and the romance of Spain’s sunny towns and black-eyed senoritas. When we assembled for briefing in the Mule Company’s offices, disillusionment began to set in.

It came in the person of Tobe Malone, a red-headed Irishman, powerfully robust, like a heavyweight boxer. He was dressed in a blue shirt, and moleskin britches. A heavy hickory cane hung over his arm. Red, as we called him, looked tough; he talked tough and we soon found he was as tough as his looks and talk. He briefed us on the responsibilities we had for our passengers. He had breezed in to where we were assembled and proclaimed: “Boys, this ain’t goin’ be no picnic we’re embarkin’ on. Work’s goin’ to be hard. When we get out to sea and have to get feed out of the hold, it’s goin’ to be hottern’ hell. Your food’s goin’ to be plain, not what you’re used to at home perhaps, but you won’t starve to death. I’ve been over 23 times and ain’t dead yet. Look at me!”

What we saw was a specimen of red-blooded manhood, two hundred and twenty pounds of it, hard as nails and not an ounce misplaced. Red’s keen, blue eyes bespoke vigor; his jaw, determination.

“You’ll have wooden bunks with straw mattresses and cotton blankets,” he resumed. “Clean when you get ‘em and comfortable, if not homelike. Ev’ry man’s got to do his work, sick or well. Jus’ cause you get seasick ain’t no sign your mules is goin’ hungry. I want you to get that good.” He paused while his steady eyes swung over the group, impaling the edict into our consciousness.

“Any questions?” Red asked. One brave soul wondered, “When do we see the mules?”

Red grinned malevolently, and said, “Follow me.” He gave a sweeping come-on sign with his right arm, turned and led us from the company meeting room onto the building’s veranda. From there we looked out on the vast expanse of the East St. Louis stockyards. On a long siding, crowded into each of the 50 boxcars were 24 long-eared tail-switching, foot-stomping (mare-jackass progeny) Missouri mules. There were 1200 and it was a breathtaking, staggering sight.

With that, a buzz of questions were thrown at Red. “What do mules eat?” “How on earth do you feed a mule?” “Do mules bite?” “Do mules get seasick?” “How do you keep from getting kicked?” “What do you do with mule shit?” etc., etc., until Red beat on the veranda floor with his big, corked-handled cane and shouted “Silence!” You’ll get your answers as we go along. Now I’ll show you where you park your asses on the train.”

Red led us to the long, impressive train parked in the nearby railroad siding. At the front were two huge diesel locomotives. Hooked behind were 50 bright red stock cars, each with its 24 mules. Then came a day coach, a diner, a Pullman, and a caboose. And who was to occupy the day coach? You’re right, it was we “Muleteers” as we soon came to call ourselves. We dumped our knapsacks and duffel bags on the day coach seats and tried to reconcile ourselves to our lot. More than one muleteer wished he had never left home.

The long haul to Norfolk, while speedy, seemed endless. The engines shrieked through towns whose inhabitants gaped or waved at our speeding special which had right-of-way over all other traffic.

One unusual incident of the rail trip remains embedded in my mind. The train halted sometime after midnight to take on water at a tank in the vastness of the Tennessee Mountains. The silence after hours of pounding the rails was intense, unbroken even by the chirp of a cricket. Suddenly, from one of the stock cars came a loud bray - a roisterous “hee haw, hee haw, hee haw!” Whereupon 1199 other mules joined in the chorus of a stock-car prison song which reverberated from peak to peak. It was eerie and the sound rolled and echoed on and on. Never had I heard anything like it. I quivered all over.

Finally, the iron rails led the long train into a Norfolk warehouse at the wharf at which was moored a huge freighter, hungry for a cargo of mules. This was the Italian tramp steamer, Monarco. She was a dirty old tramp from putting into the bottom hold thousands of tons of coal destined for Italy.

The joint ceremony of loading the mules, and initiating us into the mysteries of the Order of Muleteers, began at 5 p.m. on a broiling hot July 4th afternoon. We found loading 1200 mules on that old tub no Fourth of July picnic. A humidity of nearly 100 degrees didn’t help.

As the first mules were run through a long narrow chute extending from boxcar to ship, they were haltered by hands which never before had touched a hard-tail and driven onward and upward over a long brow to the boat deck. From there, they were driven down other brows inside the ship and through long aisles to stalls where other green and tender hands grasped halter ropes and tied the beasts to breastboards.

The progress of the mules was hurried by a score of husky, half-naked sweaty black stevedores stationed along the chutes and aisles. They prodded the animals vigorously. They yelled and swore vociferously at every manifestation of stubbornness. Clatter of hooves on steel floors, shouts and curses of the stevedores and noisy commands of bosses filled the air. The beasts in their stalls, perplexed by strange sights and sounds, brayed and lambasted each other and rumpboards with their hooves. It was utter bedlam.

We had to work in semi-darkness down on the mule decks, as we fastened halter latches, tied ropes to breastboards, and dodged nipping teeth of spiteful mules. The decks, with no circulation of air, seemed like inferno; the night, endless.

Seventeen hours after the first mule had been prodded up the runway, the last one was tied up. Then the ship blasted its departure whistle, the lines were cast off, the tug boats nudged the ship from the pier and guided it through Hampton Roads and past Cape Henry’s lightship out to the open sea.

We clambered down the stairs into our bunk room and fell wearily into our wooden bunks with their lumpy straw mattresses. Several hours later, into our deep sleep of exhaustion came a growing awareness we were not the only bunk occupants. Something was biting and the bites caused intense itching. After a half hour or so of continuous scratching, some of us took our blankets up on deck, examined them closely with our flashlights to make sure they were free of bedbugs, and spread them out on the piled high bales of hay. There we slept until dawn, when Red aroused us for the day’s work. First he gave us instructions in the use of the articles he gave each of us.

“This hand-axe is for cuttin’ wire on hay bales and for general purposes,” he said. “The bucket is for measurin’ feed for the mules, for carrying water, for washin’ yourself and your clothing, and, if the occasion arises, for bailin’ urine and manure out the stalls in the hold. Each of you’d better put a mark on it so you will know it. Your mules are thirsty. Hook your trough over the breastboard as you work along the aisle and run water in with the hose line. Give ‘em plenty, boys. Then fill up the aisles with hay. I’m countin’ on you handlin’ these mules like you would your own property, for better or worse ‘til Barcelona do you part.”

The decks below were stifling with animal heat. Sweat seemed to pour from every pore of my body. In a few minutes every thread of my clothes was wet. My feet squashed in my shoes, as if I had been wading in puddles. In desperation, I lifted the hose line from the trough and held it up so the water would pour down over my head and down my back. It was more than two hours before I had watered all my mules, broken hay out into the aisles and wearily clambered up to the deck for air. I was one of the first to emerge and hunt out the pump to wash my dirty, grimy body.

At six o’clock every morning the ship provided strangely flavored tea and hard tack for breakfast. But thanks to the generosity of the Spanish Don importing many of the mules, this was augmented by corned beef or pork and beans, scrambled eggs, canned fruit, crackers and imitation jelly - delicacies designed to maintain our energy and sustain our morale. Happier muleteers, happier mules, was the idea.

At 11 a.m. the mess boy served the midday meal consisting of macaroni with a tomato-olive dressing, beef and potatoes or beans and sliced onions with spaghetti. Codfish (which the cook laid dry upon a slab of iron and beat vigorously with a heavy sledge hammer before putting the carcass to soak) was dished out to us on Tuesdays and Fridays.

The evening meal at 5 p.m. was a repetition of the noon menu with the addition of soup, which usually contained rice, bits of macaroni, and tripe. It was heavily flavored with garlic. Ancient hard tack with pinhole eyes veiled with cobwebs was plentiful. Often a man and a worm surprised one another sharpening their teeth on the same disk of whetstone bread.

Each of us was given a tin pie pan, a metal cup, a knife, fork and spoon for service at meal time. The bread line filed past the mess boy, who served rations from dishpans in the mess hall. When our food was dished out, Warren, Roy and I usually hunted out a bale of hay to sit for 15 or 20 minutes and compare indignities endured.

As the days passed, stiff, sore muscles, and blistered hands were the ripe “fruits of labor.” The sun took its toll of tender skin. Groups gathered on the hay to share their complaints. We compared bruises on body and blows to pride. We shared our reactions to the sameness of the garlicky food, dirtiness of the ship, behavior of the mules and sadism of our bosses. Some of the language used was pungently profane. There was talk of mutiny but two of the group who had made previous trips on the Monarco speedily quelled it.

“Did you ever hear about the time the kid from New York refused to take a feedin’ order and the boss smacked his face off?” asked one.

“Yes, And once I seen Red beat a feller in the face for a full half hour for sassin’ him,” replied the other.

“Did he go back to work then?” inquired the muleteer.

“You better believe it. And with one eye swoll clean shut for a couple of days. Meek as a lamb after that! Don’t you guys think for a moment Red ain’t man enough to handle you. Lord knows what he could do with that hickory cane.”

Shifting the conversation to tragic happenings, the first veteran inquired, “Can you ever forget the trip when the feller got kicked in the head and killed by the so-called gentle mule?”

“God no!” replied the other. “He sure stepped on the gas and went to Kingdom Come in a hurry. It was ter’ble. Pulsatin’ life one minute, cold death the next! But talk about horrors! Remember that God-awful storm? A wave that looked a hundred feet high washed across the open deck and knocked down all the hospital stalls like they’re building up here now for mules. Some of the mules were killed outright. Some was washed overboard. A feller named Sim got caught ‘neath the wreckage. He was mashed up fearful and after a day of horrible suffern’ that poor devil’s light just flickered out.”

“What do they do with the dead on this boat?” asked the curious muleteer.

Red’s assistant, who had joined us, answered: “Put ‘em overboard, of course. There ain’t nothing else to do with ‘em. I’ve helped put four over myself.”

“God!” gasped one of the youngest, pale-faced and shuddering. “That’s terrible! I’d sure hate to see anything like that.”

“Hell!” ejaculated the second boss. “Ain’t nobody enjoys it, but I tell you there ain’t nothin’ else to do.”

“Do you have any kind of funeral service?” another asked.

“Sure,” rejoined the boss. “First we take the body and wrap it up good in a tarpaulin and tie weights to the head and feet, then lay it right up there on that cabin. The ship’s engine stops. They bring out the little book and read a verse. Then we just shove the corpse off and splash, it’s all over. The ship don’t stop. It just keeps on driftin’. The reason they puts weights on is to make the body sink, though it won’t go clean to the bottom. If they didn’t put weights on the corpse it would float around on top of the water and look right neglectful.”

The Monarco traveled the Southern route to better escape storms. It had no air-conditioning. The only fresh air to reach the lower decks came through two wind-sails hung in the rigging above the fore and aft deck hatch openings. The heavy canvas sails were about 10 feet in diameter. Attached to each sail was a canvas tube - 24 inches in diameter. The forward progress of the ship forced air down the tube into the lower decks. As the ocean air temperature was in the 90s, with high humidity, this provided little relief. The combination of the summer heat and mule body heat made the hold temperatures during the day well over 100 degrees.

This hot weather necessitated much extra labor. The heat produced ailing mules, which had to be moved from the over-heated decks to the hospital stalls constructed on the top deck. I was one of the muleteers chosen to spend the time between feedings at stall building. Others were ordered to prod, drag or drive the hybrids from the lower decks to the top deck.

It was usually a difficult and spectacular task to move a stubborn mule. The head boss, Red Malone, would slip a lariat over the mule’s head, grasp the rope in his powerful hands, and leverage the pulling force against the resistance of the beast. If the mule hesitated to move forward, Red hurled a crescendo of commands with the rapidity of a Gatling gun.

“Come here a lot of you fellers and swing onto the end of the lariat,” he bellowed. “Now! Pull her damn neck off! Get behind her Jones! Take my cane! Get behind ‘er and hit ‘er with the cane! Knock ‘er hind end off! Lay it on ‘er rump! Hit ‘er! Five dollars if you break the cane the next lick!”

Raining blow after blow on the rigid hindquarters of the obstinate mule, Jones made a supreme effort to win the money, but the cane held firm.

“Hit ‘er again!” roared Red. “Lay it on her fast! Faster! Watch out! She’s getting ready to kick. Don’t let ‘er kick you! Your folk’ll never see you again. Watch out, man! She nearly got you!” Jones ducked as the hoof whizzed within an inch of his head, and the mule took off down the aisle.

The weather cooled. In the stalls on the boat deck, several dozen mules with white noses deep in metal troughs hooked over breastboards in front of them, muzzled their oats contentedly.

During this period we were usually free for a couple of hours following lunch. Sometimes there were special assignments. All the water drunk by a mule doesn’t emerge as perspiration. There were scuppers in the decks back at the ship walls. They were supposed to carry off the urine. But by the time we had been at sea for about ten days, some of the scuppers clogged up with straw and manure. An ankle deep pool of liquid formed in a depression of the deck. We called it “Lake Urine.” The arising aroma would never be mistaken for Chanel #5!

Complaints from those working in that area caused Red to take action. He singled out the two muleteers he thought most sissified and gave them the onerous task of bailing Lake Urine. He sent them down to the mule deck with a couple of water buckets. Up on deck, he lowered a rope with a snap clasp at the end. One of the men standing ankle deep in urine would scoop up a bucket load, pass it to the other to snap into the clasp. Red then would pull it up, let one of us muleteers unsnap the bucket, carry it to the ship’s rail and empty it overboard while another moved to Red’s side. Occasionally, he would slop a little on us. I never heard him say “Pardon me.” On this first bucketful, though, the two boys below, stood there - their faces turning upwards as their eyes followed the bucket up. About two thirds of the way, Red’s grip on the rope slipped. He quickly pulled up on it and about half the bucket’s contents showered down on the bailer-outers. Red had a devilish look of pleasure on his face as he laughed down at them. To me, the urine-drenched hair and faces were a pathetic sight. Imposing such indignities, however, was to Red, a joyous pastime.

But we did have our pleasant moments. Most of us were crossing the ocean for the first time. It was a new and delightful experience to be sleeping on top of stacked bailed hay on deck with only a star-studded sky for cover, seemingly close enough to tuck under one, watching the sky and moody sea by day and at night watching the luminous of the waves ahead of the ship. We were amazed when a misdirected school of flying fish landed on the deck.

Mules or no mules, the ocean was wonderful when one had time to consider it. At times it was like a lady, sitting serenely with folded hands in a chair and rocking gently. Again, like one writhing in the throes of epilepsy, foaming at the lips. The day winds whipped up the spray and played rainbows with it. Little flying fishes glided like tiny silver planes, then flopped abruptly into the water, as if engine trouble had developed.

And there was always a peaceful satisfaction in the evening, knowing there would be no more work until morning. With the quiet disturbed only by the swish, swish of waves against the ship, it was wonderful to lay on your blanket on the timothy hay, looking up and watching the shooting stars, the flying fish of the heavens.

One thing learned in working with my 35 mules that I hadn’t discovered working with our farm mules was that each mule, like humans, is different. By the time our voyage ended, I was identifying characteristics in my mules which reminded me of people I knew. I named one mule Bob for a man in our church who was all smiles to your face, but loved to stab you in the back. His mule namesake opened his mouth smile-like but turn your back on him and he would nip you if he could. Another reddish colored mule I called Red for he seemed to snarl at me like our crew boss. I remember another that looked at me with soulful brown eyes like a girl I once went with named Virginia. This mule I called Ginger. She liked to have her head patted. I found myself telling my many frustrations to some of my more friendly animals. I thought sometimes I saw signs of sympathy.

So on we went, passing through the straits of Gibraltar and along the picturesque coast of Africa with its milk-white villages. A last feeding of corn and oats gave us a feeling of exultation not dampened by a squall of rain. Arching the sky, a marvelous rainbow reflected on the water and its brilliant colors reflected a circle, perfect except where the bow of the ship cut its circumference.

Oran, a great city of Algeria, was a gladsome sight as the ship glided into its harbor and was warped into its berth at the wharf. There, veiled white-robed women mingling with bronze-faced Algerian soldiers in dark blue jackets braided with red baggy trousers and red fezzes, gave color to an animated picture. There were hybrid costumes, the offspring of American and African fashions. Old horses drew dilapidated phaetons and stanhopes of styles which disappeared from America decades ago. There were big two-wheeled carts drawn by small donkeys hitched tandem. A flute player with little children dancing at his heels. Fresh, interesting sights to my eyes.

Brown-faced men in flowing burnooses, with stout hickory canes, now recognized as the badge of muleteers, soon came alongside the officially received two hundred mules which were bidden a glad God-speed as we helped run them off the ship.

Trotting briskly and turning their heads from side to side and braying at the strange sights of Africa, these four-legged Beau Gestes of Muledome disappeared over a hill to join the French Foreign Legion.

We were not permitted to go ashore, but the ship was swarmed upon by vendors with chocolates, luscious grapes, cakes, cigarettes, ice cream, wine and beer. After thousands of miles of travel deprived of such, we filled our bellies to near-bursting with tasty luxuries. We matched wits with Arabs in an improvised bazaar on deck until all of their delicacies were bought and the ship put to sea - headed for Barcelona.

Sportive porpoises had been leaping and racing ahead of the ship for several days. Ship-crew members had tried hard to spear one. Finally, one of the sailors, standing on an anchor at the bow, cast a harpoon successfully. His voice rose in an exultant cry. His fellow sailors ran forward excited, all talking at once. They grabbed the harpoon rope and swiftly hauled the big mammal up over the rail and onto the deck. It whistled its groans as the harpoon was cut from its body and flopped about until a sailor jumped astride its body and held it quiescent. He was loudly acclaimed as if his steed had been one of a sheik’s wildest Arabians. A carnival spirit spread through the crew. One of them drew a long knife and cut the throat of the animal. Its blood gushed out. With deft hands, the porpoise was butchered, its meat to be hung up and dried, its fat to produce valuable oil. Its opened body revealed a flopping baby porpoise which the sailors nonchalantly cast unharmed into the sea. We watched transfixed!

One of our muleteers was horrified. “They oughtn’t to have killed an expectant mother,” he proclaimed indignantly.

Another speculated, “Why would they kill a porpoise anyway?” It isn’t fit to eat and it’s the only friend a sailor has. Why, on an English boat, they’d mob a man who would harm a porpoise.”

“Why is it a sailor’s friend?” another wanted to know.

“Well, when a body is drowned at sea,” came the reply, “the porpoises keep nosing it along and nosing it along until it is tossed up on the beach.”

That was our last evening before Barcelona. Our ship was cutting its way through the front yard of one of the Balearic Island sisters. This daughter of Spain, Ivisa, with her chalky peaks dominating expanses of open spaces dotted with scrub pine, looked like a raw-boned peasant clad in a dingy brown dress with spots of mildew. She appeared wan-faced, unsmiling and dreaming.

I couldn’t help thinking the glories of the Mediterranean sky and water had been oversung by the poets. But as we watched the sun dip into the sea, the sky blazed with a marvel of indescribable colors. The sea shimmered with opalescent ripples as tiny as overlapping fish scales.

Ivisa, as if aware that strangers were within her gates, flushed with the excitement of choosing the most becoming gown in which to receive them. In the glow of sunset, one seemed to sense changes of expression and graceful movement as Ivisa mirrored herself in the sea and whimsically laid off draperies of pastel shades for those of smoke blue haze, which in turn were replaced with a robe of mauve. The raw-boned peasant stood transformed into a comely Spanish princess who graciously smiled a welcome to her country.

The sky smoked. The sea smiled. A muleteer smiled and said, “The whole blamed works has been so lovely I think I could just praise God and die, if Barcelona were not just over the horizon to the north.”

After the Mules in Italy

‘Lilburn Says’... a Boonville Daily News column published February 17, 1975 tells something of his experiences in Italy while the Monarco was in dry dock in Genoa for two weeks.

Rummaging in my archives the other day, I found a diary of my visits to Italy in 1938, the reward I enjoyed after nursing Missouri mules across the Atlantic to Spain.

From the diary addressed to a favorite “little bit of loveliness,” here are some excerpts:

How I yearned for you at Tivoli (a few miles outside of Rome). You would have been delighted to visit the beautiful old Villa d’Este with its magnificent old cypress trees which have never lost their slender lines, its terraces of fountains, hundreds of them, all playing. The Cardinals who lived there seemed to have had a flair for feminine figures in bronze with water sprouting from their breasts. One lady had 20 nipples, 16 of them functioning. There were water falls, swans in languid pools. And down the mountainside were grape arbors with luxurious leaves.

Renting a clip-clop [horse-drawn carriage] we drove through the little town of Tivoli and around the side and head of a canyon to the opposite side of it for a distant view of the fountains, waterfalls and vineyards. The tile stucco houses of Tivoli tinted pink, green, buff and azure crowned the mountain like a hat.

Near Tivoli are the ruins of Hadrian’s villa, a Roman emperor who lived in the years 78 to 138; its theaters, temples, baths, etc., still in a fair state of preservation. Its cypress trees showed no signs of the ravages of the ages. They whispered in sighs as the wind blew through them. I wished I could understand what tales they told.

In Florence we saw things at the art galleries until we were pop-eyed and our legs threatened to collapse. Among others in our party were maiden teachers, and an old man with a young bride who couldn’t understand why they didn’t have electric fans installed. Students pored over guidebooks, looked at the art, then pored some more.

A fat woman always lagged behind the group but would catch up just as the guide finished his explanation of a special piece of art. He had just told us of a marble figure with a funny head when she overtook us and inquired of him.

“Now, what does this big man represent?”